The importance of equity in early childhood education

In 2021, more than 63,000 children were assessed as developmentally vulnerable when they started school, according to the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC).

The census questionnaire covers children’s development in five domains known to predict health, education and social outcomes later in life (AEDC 2014). These domains are: physical health and wellbeing, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive skills (school-based), communication skills and general knowledge.

The Front Project has now conducted an analysis of this data, revealing for the first time in detail, the locations and circumstances of these children around the nation.

The analysis highlights the circumstances of disadvantage experienced by many of these children, how inequity of access to high quality Early Education and Care (ECEC) services contributes to this issue, and how we might work together with government and communities to address this serious problem.

Developmental vulnerability and what it means for our children

Most children’s brain development occurs between the ages of one and three and research shows that their early experiences set a strong foundation for learning, health and wellbeing outcomes throughout their lives.

Children can face a range of risk factors, such as a lack of access to healthy food, family stress and unstable accommodation, so protective factors, such as safe, loving parents and caregivers, and high-quality ECEC, help to protect children and reduce the impact of risks.

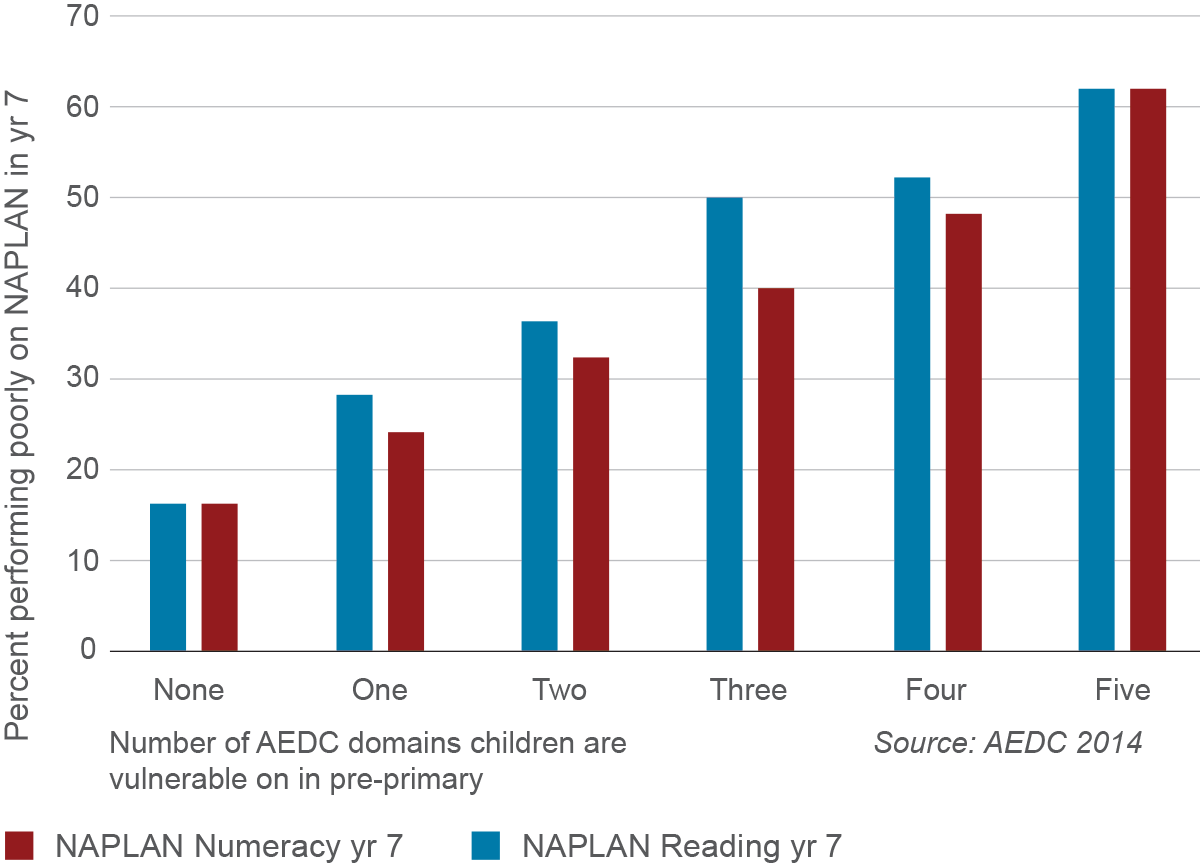

Of the more than 60,000 children assessed as developmentally vulnerable, by Grade 3 these children are a year behind their peers on NAPLAN. By Grade 5 they are on average two years behind their peers on NAPLAN.

Evidence shows that in turn, these students are less likely to finish school, and are more likely to experience unemployment and suffer ill health throughout their lives.

In Australia, your postcode or cultural background should not dictate a child’s level of developmental support, but as this study demonstrates, that is the case.

The impact of high-quality early childhood education and care

A key measure shown to reduce vulnerability is quality early childhood education. Across Australia there are thousands of children whose learning, and life outcomes, have been brought back on track with the support of quality early childhood education and care (ECEC).

Research shows that disadvantaged children stand to benefit the most from ECEC but also experience barriers to access (Melhuish et.al 2015). By supporting all children to attend quality early education, particularly those most in need, we can ensure more children have the chance to thrive.

Taking action in the early years makes sense, leading to less spending on remedial education, criminal justice and youth offending, and health services, along with significantly increasing economic productivity, to name just a few benefits.

Every child who is not thriving when they start school is a missed opportunity: an opportunity at the individual and community level to support improved development and achievement, and a missed opportunity for the Australian economy and society.

Early childhood education and care also has a central role to play in Australia’s recovery from COVID-19 not least by supporting parents to work and supporting the development of all children across Australia by minimising the impacts of the pandemic on a child’s life.

Who and where are the most vulnerable children?

The gaps and risks are far greater for some children who face multiple risk factors. Growing up in poverty is a key factor that predicts whether a child is developmentally vulnerable by the time they start school.

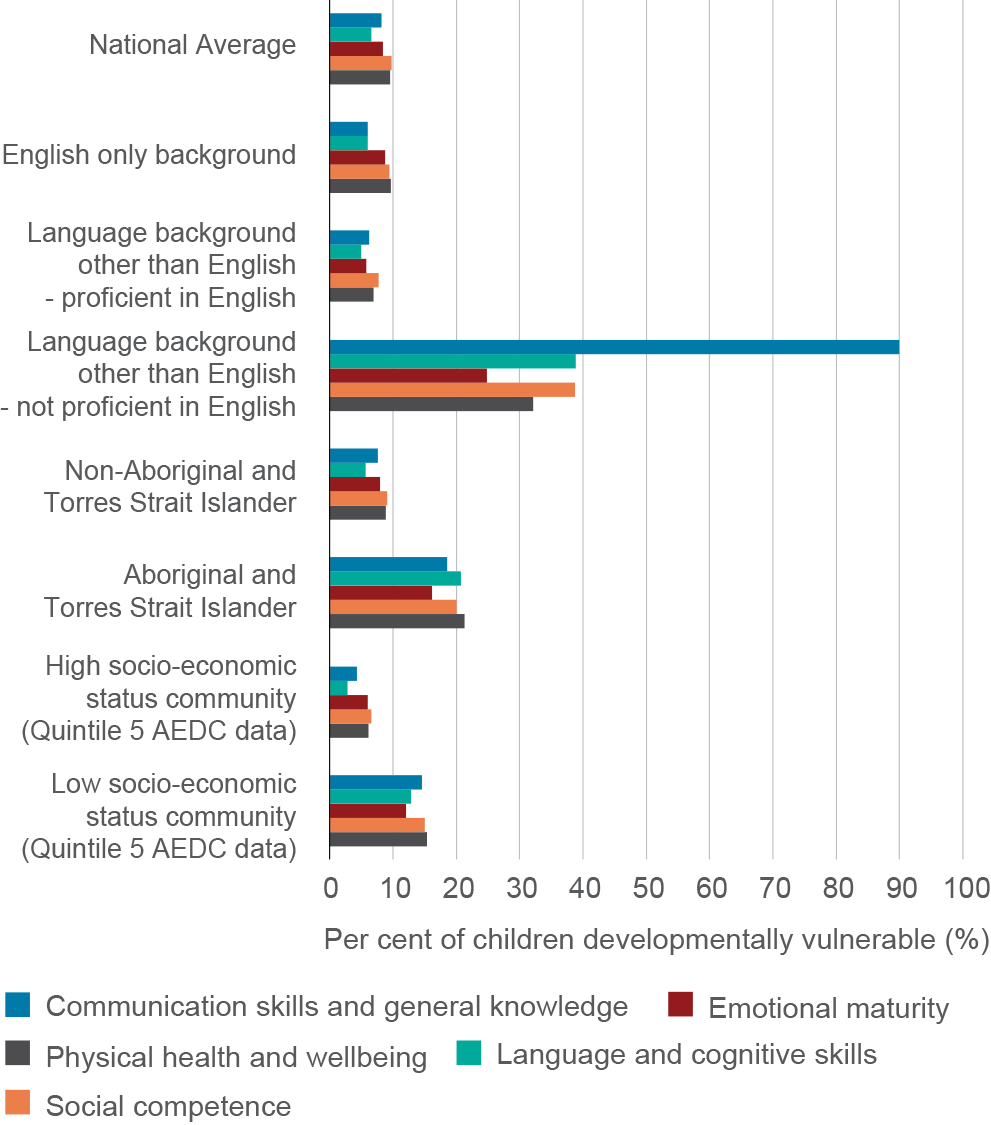

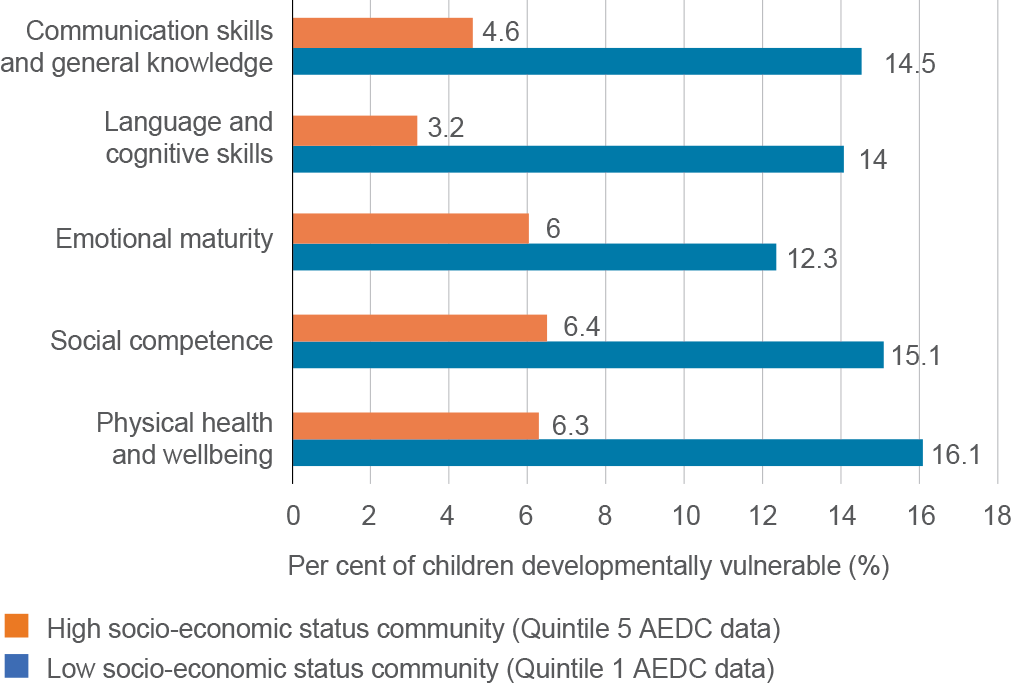

Children in the most disadvantaged socio-economic areas are twice as likely to be developmentally vulnerable (33.2 per cent compared to 14.9 per cent) and three times more likely to be vulnerable in more than one area (19.1 per cent compared to 6.7 per cent) than children in the most advantaged socio-economic areas.

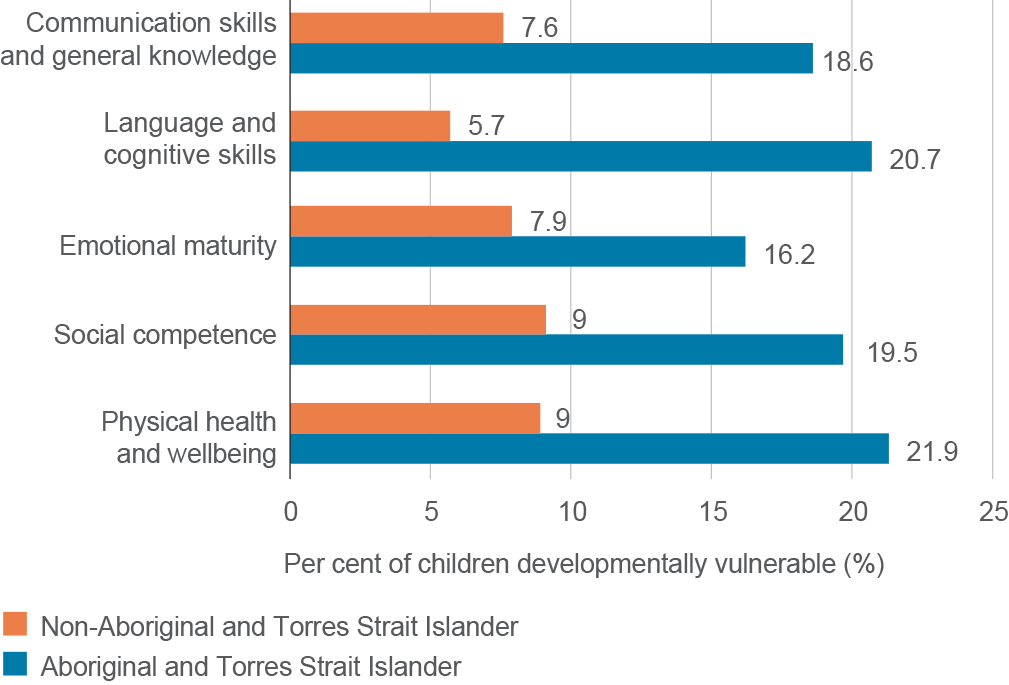

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children have high levels of vulnerability – 42.3 per cent are vulnerable on one or more domains compared to 20.6 per cent for non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children encounter more than one risk factor, including living a socio-economically disadvantaged location, and living outside the major capital cities (thus having poorer access to services and other protective factors).

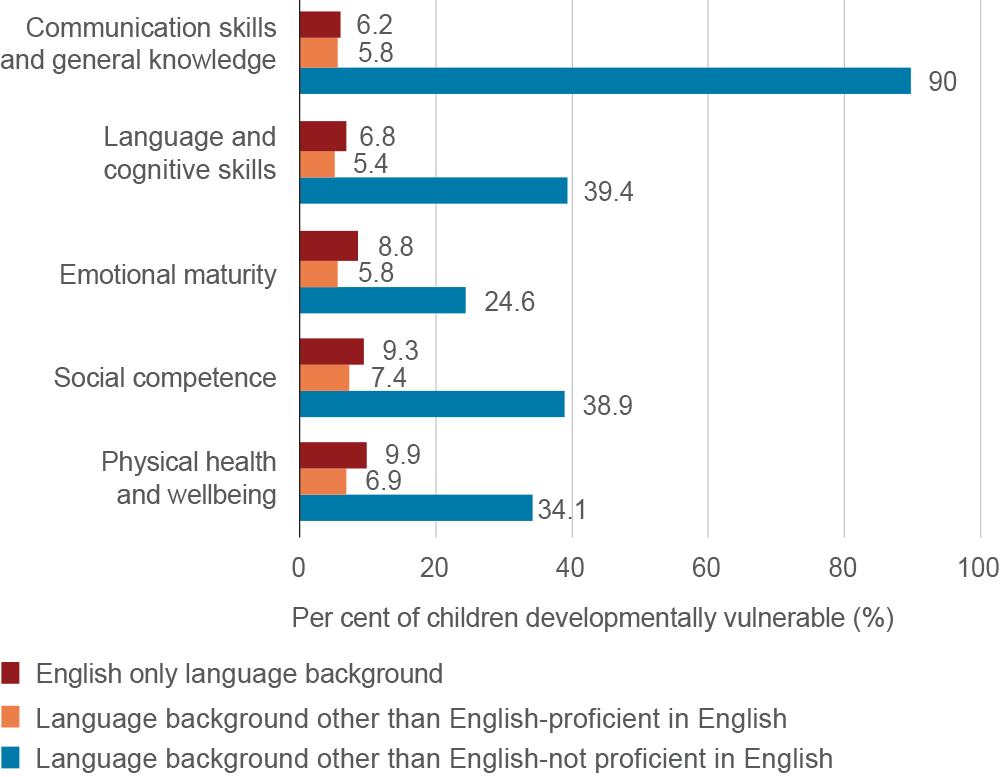

Those from language backgrounds other than English are likely to face challenges with language, especially if they are not fluent in English at the start of school. More than 90 per cent of children who are not proficient in English are developmentally vulnerable, with 60.5 per cent of these children vulnerable on more than one domain.

Government and communities working together to overcome disadvantage

A variety of policy interventions would support more children to gain access to high quality early childhood education and care.

1.Provide two years of preschool to all children, and more for those who need it. Four-year-old preschool has been a policy success story, with nearly all children attending preschool in the year before school even though it is not compulsory.

Extending preschool to two years before school, like in Victoria and for select children or locations in other jurisdictions, would provide additional opportunity for all children to prepare for formal schooling and for early intervention to support children to start alongside their peers. As the Early Years Education Program showed, the most vulnerable children would benefit from intensive early childhood education and care for more hours from an earlier age.

2.Invest in the workforce to build quality in every community. This includes governments funding the initiatives in the National Workforce Strategy (ACECQA 2021) to ensure that the workforce is built and retained. Professional salaries and conditions are needed to retain early childhood educators, and governments should look to other industries to incentivise quality staff to work in our most vulnerable communities.

3.Provide targeted support for the inclusion of all children, including through adequately funding Inclusion Support Program and improve access to high- quality ECEC for those who need it most. Targeted support is needed to ensure that services are welcoming and accommodating of children who face additional barriers to learning, including through Inclusion Support Funding that is matched to the growing needs of children emerging from the pandemic.